LET'S WORK

Together

Switch to your local agency

Retour au menu

Brand activism has been gaining prominence over the past few decades. Currently, in order to remain competitive, they must build a territory with a positive impact, adopting a clear and committed position with one or more causes. In doing so, the challenge they face is how to approach it constructively, being true to the brand’s values.

Given this situation, here are some reflections to help brands understand the different types and levels of activism, along with the risks and benefits that come with them. Paths that, if followed with truth and transparency, can lead to a real and lasting commitment.

Since each brand is different, we categorized several activism profiles according to the brand DNA and the relationship it intends to maintain with its stakeholders:

Superactivists: Activist brands since its creation, committed to causes related to its fundamental values, which are supported by the founding partners or general managers. They truly aspire to achieve social change and create a strong emotional bond with their followers, so much so that they often become brand ambassadors. The most well-known and successful example may be Patagonia, the outdoor lifestyle brand committed to environmental causes whose “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad encourages people to reconsider impulsive shopping. Ben & Jerry’s (Unilever) also stands out for being a brand committed since its inception to different social causes.

Paradigm Breakers: Innovative and pioneering brands in their markets. Their products and services are their hallmark of activism, as they are born expressly to change patterns. They forge an emotional bond with their consumers by meeting previously unmet needs.

Examples include Impossible Burger and Future Farm, innovative brands in the meat substitutes sector. Its mission is to reduce the environmental impact and encourage the consumption of plant-based protein.

Daring: They are the brands that, although not being so open and constantly committed, they defend their values and causes in a coherent way. They lead attractive actions and are agile in taking a stand on current issues that fit and connect with their values, joining the conversation and fostering debate. For example, Starbucks in the United States has been involved in social justice issues, banning guns in its stores, supporting same-sex marriage and fomenting debate about racism.

Responsible: Companies where brand activism is not evident in their pillars or communication channels, but is part of the brand territory. It is a more traditional and discreet commitment, without generating conversation or controversy. In addition to taking corporate action, these companies are aware that their product portfolio must be aligned with sustainability and latent requirements to promote real change in society and on the planet. Adidas, launched its iconic Stan Smith x Mylo sneakers, with a material made from mushrooms that offers an alternative to animal leather, thus producing its first sustainable shoes.

Strengthen internal engagement: gain internal support and attract new talent.

Increase awareness: raising your voice can be more effective than traditional propaganda to draw attention and have exposure on social media with relevance and truthfulness.

Increase loyalty: show intentional engagement so consumers can help build loyalty and cultivate a strong emotional relationship.

Win new consumers: positive attitude and actions can be that plus to convince more people to experiment with the brand’s products and services.

Increase sales: brand action can lead ambassadors/followers to boycott, deliberately seeking to stimulate the purchase of your products/services.

Trigger internal conflicts: not all employees may share their brand opinion or engagement in a cause, primarly if it is politics.

Discourage the founders or the board: taking risks is not usually well seen in the financial market, being able to lead to loss of stock market value or losing endanziation.

Encourage cancellation: be canceled on social media, such as generating controversy in brand feedback and not being liked by everyone (or a significant part of your followers) because it is considered incorrect or in bad taste.

Incite boycott: moment of rejection of the brand. Remember that a reputation stain can remain in the brand’s history (or on the Internet) forever.

Losing consumers: the opinion of a brand can degrade so much that some consumers, who are not very loyal, may drastically prefer the competition.

We suggest 8 steps to achieve it:

1. Define a clear and powerful brand positioning: What is the reason to be of the brand, its beliefs? What is its DNA, personality and target audience?

2. Choose your battles: It is necessary to identify the causes in which it will have credibility. They must be aligned with the core values of the brand.

3. Define stakeholders: In addition to the target audience and consumers, who else does the brand impact, directly or indirectly, externally or internally? Stakeholders include employees and their families, the board of directors and investors, influencers, specialized media, government and social partners.

4. Look at the brand’s track record (and its present moment): Although the brand purpose may have evolved over the years, the past cannot be ignored. It is important to review previous actions, statements and campaigns to assess the credibility in committing to a particular issue.

5. Define the brand activism profile: Feedback from stakeholders deserve attention. The brand must learn from its mistakes and successes and act quickly.

6. Identify potential risks: The more renowned the brand is, the more important it is to assess the risks and benefits of taking a stance – or of staying neutral.

7. Walk the talk: Promises, great speeches or fierce campaigns are not enough to guarantee a brand’s survival without significant and real actions to support them. Consumers expect the brand to engage in a realistic and tangible way, and if it doesn’t, they will ask for it.

8. Listen to feedback: Feedback from stakeholders deserve attention. The brand must learn from its mistakes and successes and act quickly.

It is proven that activism is not an ephemeral trend, but a change in today’s society. Therefore, despite the fact that each brand and market is in totally different situations, it is essential to start acting and transforming in order to successfully adapt to the upcoming.

Thorny and divisive issues, which are linked to the political or moral sphere, have often been seen as taboos for large companies. The risk of negative repercussions in being the bearers of critical or controversial messages has very often deterred brands and entrepreneurs from taking a stand for or against a particular cause.

Something has changed.

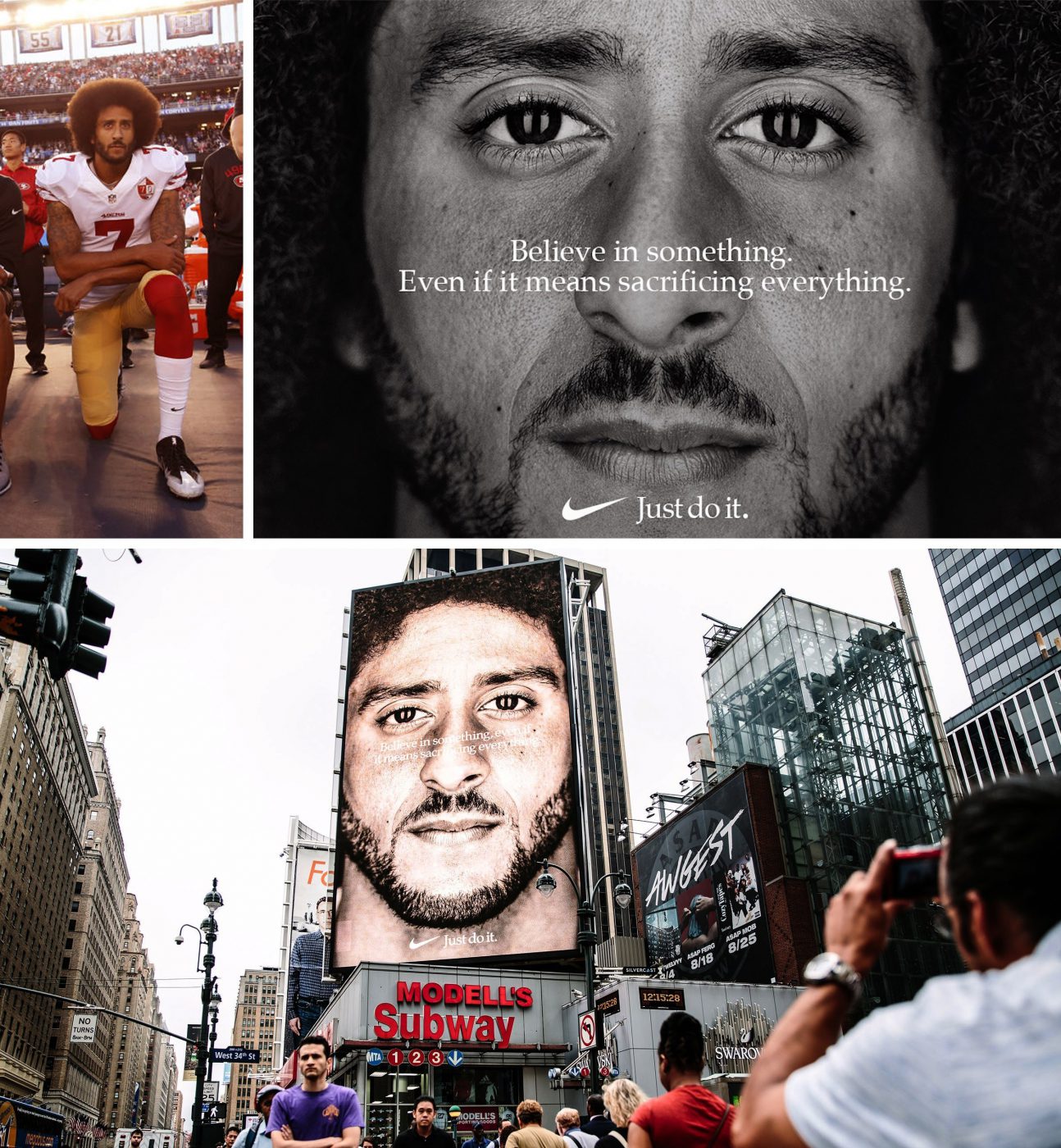

One of the most striking cases is that of Nike with the campaign of quarterback Colin Kaepernick, a symbol of the struggle against African American oppression. Since 2016, he has been excluded from the National Football League after protesting against police violence against African-American youth by remaining seated during the national anthem. Following the campaign, videos of people burning their Nike trainers appeared, but also, apparently, a majority of positive feedback on all social networks with a final result in terms of visibility which was very relevant.

Another important example of “taking a stand” on political issues is the “Rainbow is the New Black” campaign produced by Netflix last June to commemorate Gay Pride in Milan, where the Porta Venezia subway station was covered with rainbow colors and photos of many gay stars from the Netflix TV series. It is not only about supporting the cause of the recognition of the rights of the LGBTQ+ community, which has always been noticed in Netflix’s programming, but also, and more importantly, the desire to be part of an event like Pride, which had been severely attacked by the Italian Family Minister by being taken as a direct target of the campaign.

There are examples of those who try to take this step but fail: Pepsi has been harshly criticized for a video ad in which supermodel Kendall Jenner, in the midst of a “protest rally”, hands a Pepsi can to a policeman bringing peace between the two sides. Critics have violently hit out at the commercial, which seems to exploit and trivialize the imagery of the Black Lives Matter movement for its own economic advantage.

Another example that ended rather badly: the music magazine Rolling Stone, which appealed against the government’s migration policies that had just been set up in July, dividing public opinion a lot and then disappointing everyone with the discovery that many signatories for the appeal had been added without even knowing it.

An initial reason seems to be linked to the social role that consumers attribute to private companies: more and more people expect that social change must come from them rather than from public institutions. 88% of Americans think that companies actually have the power to produce social change (SONAR, 2016). This trust in companies, which is often opposed to the scarce accountability of public institutions, is linked to the perception of being able to influence them with our purchasing behavior. In fact, another survey reports a striking fact: in 2017 50% of Americans participated in at least one boycott during the year, with a 20% increase compared to 2016 (K. Endres, C. Panagopoulos, 2017). This change in perception of the social role of brands, contrary to the classical belief that ethics and business go in opposite directions, has led some economists such as Chris Ladd to talk about Social Capitalism: an economic system in which people consider purchasing not as an exchange of goods but as a vote. The field of competition between the brands seems to have extended to politics, leading companies to have a position on social issues in such a way as to “be voted for”.

Another reason is related to the political context itself, which sees brands forced to take a stand in the face of radical or extremely divisive government policies, which often also directly impact the companies’ businesses, as has happened for the “Muslim Ban” wanted by Donald Trump. In January 2017, the ban on citizens entering the US from the 7 nations with an Arab majority saw a harsh public reaction from the tech giants of Silicon Valley who have the best brains from all over the world among their workforce. Google, Facebook, Apple, Uber, Microsoft, Netflix and many others have condemned the provision, referring not only to the negative consequences for the development of their companies but also to the fundamental principles of inclusion and openness that have made the US the power that it is today.

It is not always easy to tell if and when it is appropriate for brands to risk exposing themselves. Bloomberg has quantified the value of the media exposure generated in 24 hours, after Kaepernick’s Nike commercial appeared on Twitter, at $43 million. This is the case even though the President of the United States, D. Trump, has called it a commercial that “gives a terrible message”. Certainly when Nike made this decision it did so on an informed basis, knowing its own user base – mostly under 35, of different ethnic origins (NPD Group) – and aiming to get through to them in the classic Nike style that has always focused on disruptive athletes since the 1970s.

Perhaps here lies the key that distinguishes cases of successful political activism from failed ones. “In classic Nike style” means that the brand has taken on a position which is consistent with itself. Because Kaepernick “just did it”, he believed in something and did it at any cost.

It is possible for brands to do “politics”, as long as they take on a position that is consistent with their purpose, their raison d’être in the world in terms of society. In a context where mistrust in institutions is at its highest levels and governments are implementing divisive and polarizing policies, a new space for action seems to open up for brands, however not everyone always has something to say.

Political activism must be aligned with values, communication and the vision of the brand world.

Since the launch of BBVA‘s new image on April 24th of 2019, there have been many comments about it. By default, criticism. And the fact is, in general, we are more about destroying than building. The day this changes, we’ll move forward by leaps and bounds.

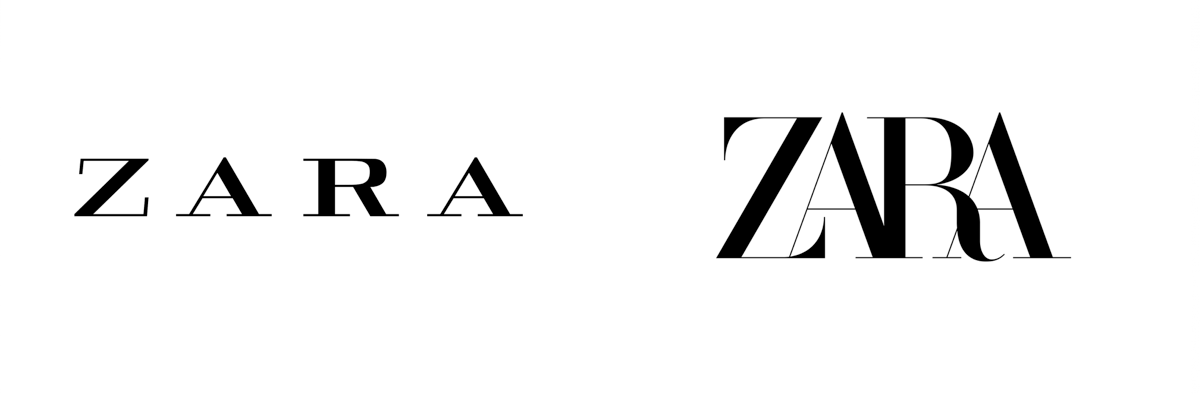

But what is the main difference between the revolt surrounding the change of Zara’s logo and the change of BBVA’s identity?

While Zara is a brand that touches our skin and connects directly with us, BBVA represents a further, even colder place, whose main purpose is to keep our capital safe. And is that what inspires us?

The purpose of branding is mainly to iconize the story we want to tell efficiently. A story that connects with who we are addressing. A story that matters to those who we are going to tell it to. So, before falling back into the like/not like, let’s think: why have they done it? What do they want to convey with this change? What do they want to tell people today, that they weren’t telling them yesterday? Then we will be able to assess how and if the aesthetic interpretation and the creative territory chosen is aligned with what attracts their current and potential customers.

According to their official statement, the need for change comes because ‘‘In a world where digitalization and globalization are already a reality, customer experience is the most important factor for the success of any company.” Well, here we find two key leads:

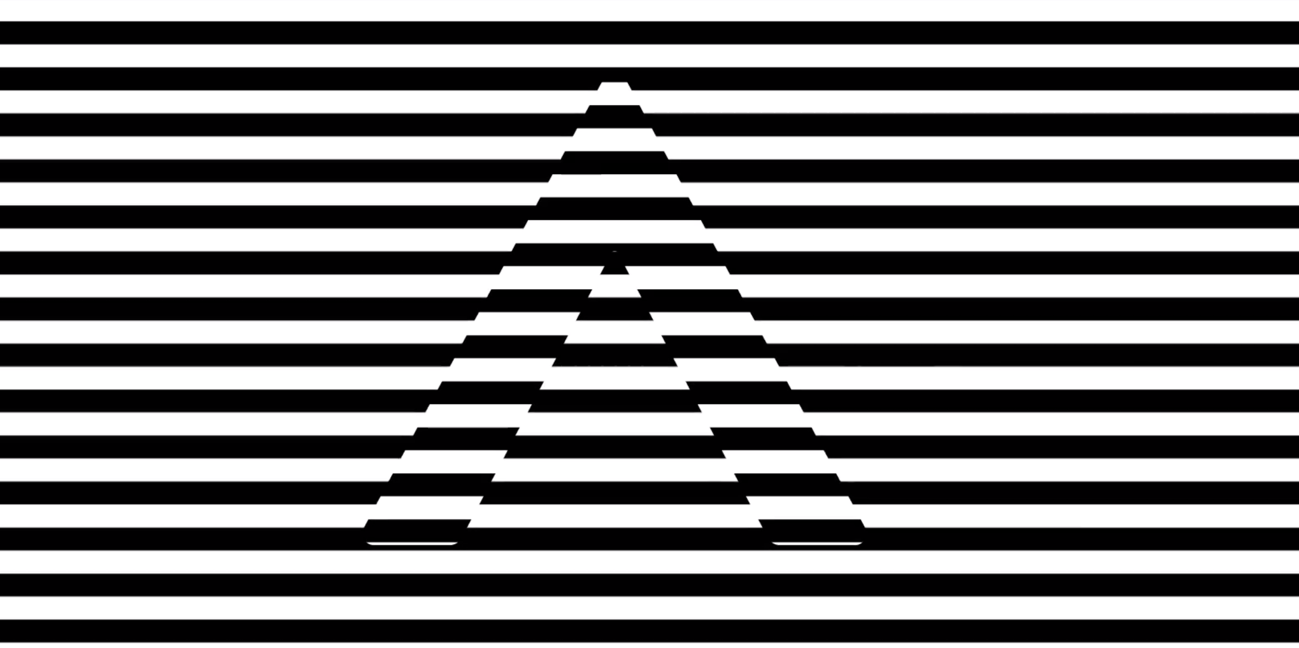

All this, from simplicity and iconicity. Two fundamental ingredients in visual communication to give visibility and recognition to a brand. In this case, capitalizing on the tagline ”Create opportunities”, allows to develop a chameleonic aesthetic language as an invitation to discovery and creativity. A proposal that seeks to stimulate and inspire, and thus connect with younger audiences. An exercise that other brands have carried out throughout their history, and that is sustained, mainly, thanks to the construction of a simple but consistent icon.

And the fact is that the versatility of a brand can only be built through iconicity. That is why it is essential to find a symbol that clearly represents what we want to tell.

In the case of BBVA, one of the major changes has been to build on the ”A” as an icon of the brand. ”A” as an open door to creativity and future ideas. ”Au” as a symbol of growth and solidity. The summit. A necessary exercise to be able to have an appropriable speech (with A) that revolves around what matters to people: that their money will always be safe. Because, after all, design is empathy.

Article published on MarketingNews

This is the reaction to the redesign of ZARA, one of the most famous Spanish brands on the international scene. Since the company launched its new identity last Monday, two consecutive questions have been generated in any talk between brand experts. Have you seen it? Do you like it?

I intuit that the same thing has happened among your most loyal followers, and it turns out that the general reaction revolves around the same, strange faces. Why?

This is the luck (or bad luck) of branding, of a typography, of a form, of a color, or of any composition. How a series of elements, apparently subtle, are determinant to reflect the personality of a brand and what we perceive of it.

Some people say we think in words, others say we think in images. In any case, as Matt Mullican (one of the most influential artists in contemporary art in recent years) says, we think in emotions.

And these are the only ones that always give us a clear verdict of what we feel before what we see. That’s why people’s spontaneous reaction to a brand change is so valuable, because it connects or disconnects them from it.

In the case of ZARA, the discomfort generated by the new logo may have its origin both on form and substance. The first lies in a complicated interpretation of the aesthetics of the publishing world in fashion, in addition to its indisputable similarity to the logos of VOGUE or HARPER’S BAZAR (the latter designed by the same agency).

According to the agency responsible for the project, ZARA’s new identity seeks to ”elevate its image and bring it closer to the standards of contemporary luxury”. An exercise that bets on getting rid of the negative connotations associated with the low-cost concept to speak now in terms of ”democratization of art and fashion”. A nuance that changes the course of ZARA’s positioning, or at least that’s what we interpret. The debate could be on whether it is coherent with the brand and product or even whether it is credible and legitimate to share an aesthetic language with Dior, for example.

In any case, Fashion brands are not the only ones facing this kind of challenge, apparently easy to judge. Google, for example, created more than 2,000 doodles over the years and has changed its official logo no less than seven times. And yet it has achieved a brilliant branding exercise based on the iconicity, still preserving its identity, recognition and connection with its public.

Article published on MarketingNews and El Publicista.

Subscribe and receive CBA’s latest news!

CBA Design Spain is part of Ogilvy Spain and WPP, a global communications service leader.

Contact us through [email protected]

Tel: +34 93 495 55 55

Bolivia St, 68 – 70

08018 Barcelona

Ríos Rosas St, 26

28003 Madrid

© CBA DESIGN 2024

Privacy Overview